COVER STORY

The Warrior Gentlemen: Samurai Exhibit

Through more than 160 objects — armor, weaponry, paintings, lacquer ware, ceramics, costumes, and more — San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum takes an intimate look at the lords of the warrior class of feudal Japan, circa 1300-1860. A Siliconeer report.

(Above): Domaru gusoku-type armor, red cord lacing, worn by Hosokawa Nobunori (1676–1732), Japan. Edo period (1615–1868), 18th century. Iron, gilt bronze, metal, tooled leather, lacquer, silk embroidery, braided silk, fur, feathers. Eisei-Bunko Museum, 4098. (Above): Domaru gusoku-type armor, red cord lacing, worn by Hosokawa Nobunori (1676–1732), Japan. Edo period (1615–1868), 18th century. Iron, gilt bronze, metal, tooled leather, lacquer, silk embroidery, braided silk, fur, feathers. Eisei-Bunko Museum, 4098.

(Right): Portrait of Hosokawa Sumimoto (1489–1520), by Kano Motonobu (1476–1559); inscription by Keijo Shurin (1440–1518), Japan. Muromachi period (1392–1573), 1507. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Eisei-Bunko Museum, 466. [EISEI BUNKO photos]

The mystique of the samurai, Japan’s ancient warrior-gentry, has cast a powerful spell on the West for a long time. It is not only their lethal warrior-like qualities, but also their readiness to die to protect their honor that has made them seem larger than life, giving them a reputation for fierceness that has been augmented by fiction and films — one thinks of the popular fiction of James Clavell and films like Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai to Tom Cruise’s The Last Samurai.

But there’s more to the Japan’s warrior gentry than war, though that’s an important part. Being a warrior gentleman in feudal Japan also meant a sensitive and refined appreciation of the arts. As 18th century samurai-scholar Izawa Nagahide eloquently put it in his Instructions for Japanese Men:

Culture and arms are like the two wings of a bird, so just as it’s impossible to fly with one wing missing, if you have culture but no arms, people will slight you without fear, while if you have arms but no culture, people will be alienated by fear.

In a special exhibition, Lords of the Samurai (June 12- Sept. 20), San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum takes an intimate look at the daimyo (literally “great name”), or provincial lords of the warrior class in feudal Japan (circa 1300-1860). Trained to be fierce fighters, daimyo also strove to master artistic, cultural, and spiritual pursuits.

Through more than 160 objects — armor, weaponry, paintings, lacquer ware, ceramics, costumes, and more — this special exhibition explores the principles that governed the culture of the samurai lords. Nearly all of the objects in the exhibition are from the collection of one of the most distinguished warrior clans, the Hosokawa family. This collection is housed in Japan’s Eisei-Bunko Museum in Tokyo and in the family’s former home, Kumamoto Castle on Kyushu island, Japan. Seven of the artworks on view have been designated Important Cultural Properties, the highest cultural distinction awarded by the Japanese government. Three of the artworks are designated Important Art Objects, another prestigious distinction awarded only to works of notable artistic and historical significance.

Due to the fragility of some of the artworks, a rotation Aug. 3 will refresh the exhibition; some works will be removed and will be replaced with others. More than 100 artworks will be on view in each rotation, and each will include a selection of the Important Cultural Properties and Important Art Objects.

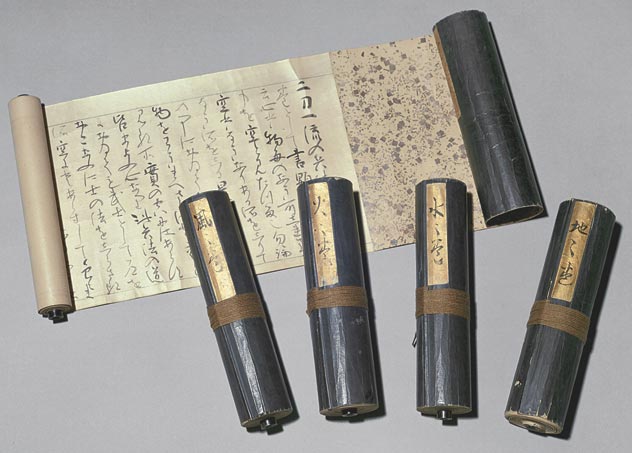

(Above): The Book of Five Rings (Gorin no sho), five volumes, by Terao Katsunobu, Japan. Edo period (1615–1868), 17th century. Set of five handscrolls; ink on paper. Eisei-Bunko Museum, 774. [EISEI BUNKO photo]

“This exhibition marks the first time that the Hosokawa family’s heirloom arms and armor, paintings, and decorative and applied art objects have been shown in a comprehensive way in the United States,” says former Japanese Prime Minister Hosokawa Morihiro, who is the regent of Eisei-Bunko Museum and the eighteenth-generation head of the Hosokawa family. “I am grateful to the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and everyone else who has collaborated on this project for providing us with this valuable opportunity. It is my profound hope that by showing the people of San Francisco and beyond the wide range of art works that have been preserved and handed down within the Hosokawa family, we will be able to promote deeper understanding in America of Japanese culture and contribute to the friendship between our nations.”

“Lords of the Samurai reinforces the Asian Art Museum’s reputation for providing quality exhibitions comprising outstanding artworks that tell remarkable stories,” says Jay Xu, director of the Asian Art Museum. “The exhibition provides the opportunity to explore the lineage of a warrior-gentleman family that dates back 700 years. Through the stories of the Hosokawa family, illustrated through their superb collection, we can understand the nature of the upper echelon of the warrior elite in early modern Japan.”

The Hosokawa family traces its lineage of military nobility back seven centuries. Only the imperial family and a few select daimyo families have histories extending back even a few hundred years. The Hosokawa family tree includes courageous fighters, poets, tea masters, regional land administrators, a former governor, and a former prime minister — most of whom were patrons of the arts. The stories of family personalities are brought to life through the works on view in Lords of the Samurai. Together the stories and artworks paint a portrait of the classic samurai warrior-gentleman — fierce in battle and refined in the arts.

This special exhibition opens in the museum’s Lee Gallery (ground floor) where a suit of armor — one of six suits on view — takes center stage. This suit is a reproduction of the famous armor worn by the founder of the Hosokawa clan, Hosokawa Yoriari (1331–1390). The authentic reproduction was made at the order of the eleventh-generation daimyo, Hosokawa Naritatsu (1789–1826), during a time when such reproductions were fashionable. This armor is of a type used primarily for one-on-one mounted combat. The armor’s heavy ornamentation and detailed decorative elements made it suitable for funeral attire as well, should the wearer be defeated in battle.

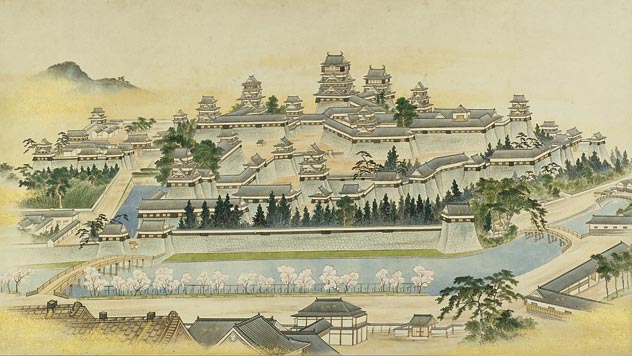

(Above): Kumamoto Castle, by Akahoshi Kan’i (1835–1888), Japan. Meiji period (1868–1912), 19th century. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on paper. Eisei-Bunko Museum, 1028. [EISEI BUNKO photo]

Lee Gallery also includes an introduction to Kumamoto Castle, the family home of the Hosokawas for more than 200 years. Considered one of the most beautiful castles in Japan, Kumamoto is on the island of Kyushu. During the exhibit different hanging scrolls will illustrate the castle’s grounds and fortifications. The castle included two main towers — one of them six stories high with forty-nine turrets, eighteen turret gates, and twenty-nine other gates; moats; and surrounding walls curved outward at the top. Such defenses discouraged attempts to scale the castle walls.

Portraits of many of the Hosokawa samurai lords and their family members are also on view in the Lee Gallery. A portrait by master painter Kano Motonobu (1476–1559) of Hosokawa Sumimoto (1489–1520) mounted on horseback is a highlight of the first rotation. An inscription above the mounted figure by Keijo Shurin (1444–1518), abbot of Nanzenji Temple in Kyoto, dates the portrait to 1507. The inscription glorifies Hosokawa Sumimoto for possessing both bu (warrior) and bun (arts and culture), qualities that defined the classic warrior-gentleman:

Hosokawa Sumimoto, a great archer and horseman, is far above other humans. He is also versed in waka [a form of Japanese poetry] and appreciates the moon and the wind. . . . Outside the citadel he takes bows and arrows; in meditation and reading of sacred books he protects Buddhism. Inside and outside, pledging to the mountains and rivers for the sake of the rulers and vassals, always with propriety and benevolence, he attains saintly wisdom.

Lords of the Samurai continues in Hambrecht Gallery with a focus on weaponry. Included in this gallery are lacquered wooden saddles, stirrups, cavalry banners, and folding screens that depict equestrian scenes. These works attest to the high regard that samurai lords placed on strong, well-bred horses for the essential role they played in battle. Blades, sword guards, elaborately decorated sword mountings, a matchlock gun, and a gunpowder container are also on view. Although all of these tools of war served a deadly purpose, their value goes beyond their functionality. The embellishments of these weapons and of their accessories elevate them to works of art. Even a piece seemingly as straightforward and of such humble materials (typically forged iron or bronze) as a sword guard — which balances the blade and hilt of a sword and protects the wielder’s hands from slipping onto the blade while it is in use — was an outlet for the samurai’s appreciation for artistic detail. A fine example of such a sword guard is one with a design of broken fans and cherry blossoms executed in inlaid gold cutouts on an iron ground. The sophisticated inlay detail technique identifies the work as that of Hayashi Matashichi (1613–1699), master metalsmith from the Higo region (now Kumamoto prefecture). This sword guard is viewed as one of the masterworks of Higo metalwork. Other works on view in Hambrecht Gallery illustrating the military aspects of the samurai lords include fans, costumes, helmets, and armor.

(Above): Mounting for a short sword (wakizashi) with spiraling bands, Japan. Edo period (1615–1868), 17th–18th century. Lacquer, lacquered wood, gilt bronze, ray skin, iron, gold, copper alloy, braided silk. Eisei-Bunko Museum, 2906. [EISEI BUNKO photo]

Osher Gallery opens with a group of objects related to Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645), the greatest samurai swordsman of his day — perhaps of all time. Musashi, who served as sword instructor to the Hosokawa family, founded and perfected the Niten Ichi school of swordsmanship, in which a long and a short sword are used together. In addition to being a renowned warrior, Musashi was also an accomplished painter. Paintings by him as well as some of his wooden swords are on view. Osher Gallery continues with other martial works, including the remaining two sets of armor and, notably, a sword inscribed by sword manufacturer Moriie, renowned for the distinctive temper lines on his blades. As the symbol of the warrior himself, a sword — called “the soul of the samurai” — was deemed sacred. Accorded the highest status among the daimyo’s luxurious possessions, swords were the items most frequently given as gifts among the military houses. The Hosokawa clan collected many fine swords.

Artworks interpolated among the military objects of Lords of the Samurai hint at the cultural side of the warrior-gentleman. Arts and culture become the main focus for the remainder of the exhibition. When not in battle, the samurai lord participated in activities such as painting, poetry, theater, the Way of Tea (tea gatherings), and spiritual pursuits. Many samurai lords were not only consumers of art but also inspired artists themselves. Among the lacquer ware on view in the exhibition is a picnic set made by Hosokawa Sansai (1563–1645). This ingeniously conceived picnic set is composed of an eggplant-shaped sake flask, a food container, and a sake cup (in the shape of an eggplant leaf) attached to the bottle stopper. The ability to execute such a complex and well-proportioned piece was a rare quality even for a cultured warrior. The exhibition continues with costumes and masks used in Noh plays (a traditional form of Japanese theater originally performed for, and sometimes by, members of the samurai class), and in Kyogen plays (often comedic in nature and performed during interludes between the more formal, sometimes austere Noh works).

Hosokawa Sansai (1563–1646) was one of the family’s most important tea practitioners. He was one of seven disciples of Sen Rikyu (1522–1591), the influential tea master who perfected the Way of Tea (chanoyu). The tradition of chanoyu, maintained throughout the many generations of the Hosokawa family, continues to be observed in the family to this day. Former prime minister Hosokawa Morihiro (born 1938), the eighteenth-generation head of the Hosokawa family, is a celebrated tea practitioner. He has also won worldwide acclaim for his skill as a ceramist and calligrapher. A few of his tea bowls and other tea ceramics are among the many on view in the exhibition. Tea containers, kettles, and other utensils of various origins are also on view.

Lords of the Samurai concludes with a section devoted to the spiritual pursuits of the samurai lords. Zen Buddhism particularly appealed to Japan’s warrior class. Its teachings of self-reliance as the essential means by which to attain enlightenment resonated with these professional fighters. Many of the Zen paintings on view are attributed to prominent priest-artists such as Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768) and Sengai Gibon (1750–1837).

For more information on the Asian Art Museum, call (415) 581-3500 or visit www.asianart.org.

|