|

|

|

ADVERTISEMENTS

|

|

PREMIUM

- HAPPY HOLIDAYS!

- Siliconeer Mobile App - Download Now

- Siliconeer - Multimedia Magazine - email-Subscription

- Avex Funding: Home Loans

- Comcast Xfinity Triple Play Voice - Internet - TV

- AKSHAY PATRA - Bay Area Event - Sat. Dec 6

- Calcoast Mortgage - Home Loans

- New Homes in Silicon Valley: City Ventures - Loden Place - Morgan Hill

- Bombay to Goa Restaurant, Sunnyvale

- Buying, Sellling Real Estate in Fremont, SF Bay Area, CA - Happy Living 4U - Realtor Ashok K. Gupta & Vijay Shah

- Sunnyvale Hindu Temple: December Events

- ARYA Global Cuisine, Cupertino - New Year's Eve Party - Belly Dancing and more

- Bhindi Jewellers - ROLEX

- Dadi Pariwar USA Foundation - Chappan Bhog - Sunnyvale Temple - Nov 16, 2014 - 1 PM

- India Chaat Cuisine, Sunnyvale

- Matrix Insurance Agency: Obamacare - New Healthcare Insurance Policies, Visitors Insurance and more

- New India Bazar: Groceries: Special Sale

- The Chugh Firm - Attorneys and CPAs

- California Temple Schedules

- Christ Church of India - Mela - Bharath to the Bay

- Taste of India - Fremont

- MILAN Indian Cuisine & Milan Sweet Center, Milpitas

- Shiva's Restaurant, Mountain View

- Indian Holiday Options: Vacation in India

- Sakoon Restaurant, Mountain View

- Bombay Garden Restaurants, SF Bay Area

- Law Offices of Mahesh Bajoria - Labor Law

- Sri Venkatesh Bhavan - Pleasanton - South Indian Food

- Alam Accountancy Corporation - Business & Tax Services

- Chaat Paradise, Mountain View & Fremont

- Chaat House, Fremont & Sunnyvale

- Balaji Temple - December Events

- God's Love

- Kids Castle, Newark Fremont: NEW COUPONS

- Pani Puri Company, Santa Clara

- Pandit Parashar (Astrologer)

- Acharya Krishna Kumar Pandey

- Astrologer Mahendra Swamy

- Raj Palace, San Jose: Six Dollars - 10 Samosas

CLASSIFIEDS

MULTIMEDIA VIDEO

|

|

|

|

|

HONOR:

A Poet and A Rebel: A Tribute to Ved Prakash Vatuk

Scholars, friends and admirers gathered in May for a special tribute to poet, linguist, anthropologist and activist Ved Prakash Vatuk, writes Kira Hall, who edited a 21-essay festschrift in honor of Vatuk.

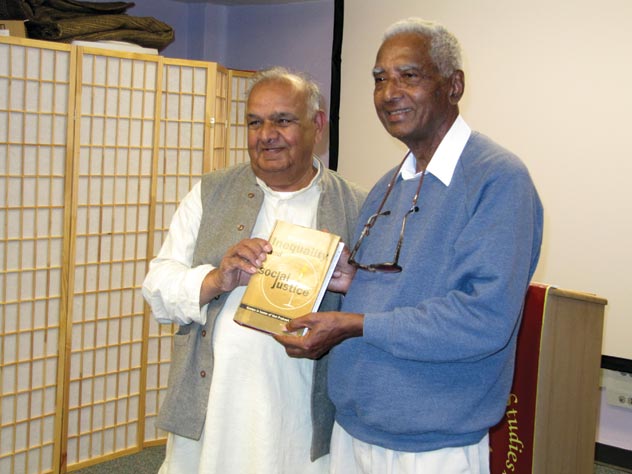

(Above): Poet folklorist Ved Prakash Vatuk (l) with South Asian scholar and UC Berkeley Emeritus Professor Padmanabh Jaini at the launch of “Studies in Inequality and Social Justice: Essays in Honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk,†at the Center for South Asia Studies, University of California at Berkeley.

When I walked into UC Berkeley’s Center for South Asia Studies on a Wednesday afternoon in May and saw a large crowd gathered, I was overwhelmed with memories of my experiences on the Berkeley campus as a graduate student during the mid-1990s. In front of me were many of the scholars and professors who had inspired me to pursue a lifetime of research on language and society in South Asia, among them my extraordinary Hindi teacher Usha Jain as well as Emeritus Professor of Buddhist Studies, Professor Padmanabh Jaini. Also present were several of the contributors to the edited volume whose publication we were celebrating: Gerald Berreman, James Freeman, Ashok Bardhan, Raka Ray, Sharat Lin, and Maharaj Kaul. Like myself, each of these scholars had been moved by the life and work of poet, essayist, linguist, folklorist, and frequent Siliconeer contributor Ved Prakash Vatuk. The author of over thirty internationally recognized volumes of poetry as well as hundreds of political essays and academic articles, Vatuk has produced an influential body of work that is intimately grounded in his life-long quest for social justice. The festschrift that I and twenty other authors put together in his honor, Studies in Inequality and Social Justice, similarly seeks to expose the diverse mechanisms that underlie and create social disparity.

But that afternoon of May 20 differed from my graduate school memories of South Asia Studies events in one important respect: Ved Vatuk was himself present in the crowd, returning to UC Berkeley to give a talk for the first time in twenty-eight years. Vatuk’s relationship with the university had become strained in the early 1990s after he wrote a series of letters and editorials criticizing the department of South and Southeast Asian studies for biased hiring practices. I met him shortly after those painful discussions had ended, when I returned from a year of language study in Varanasi with scores of field recordings. A small note posted on a bulletin board in Dwinelle Hall caught my eye. “Hindi Instruction,†was all it said, with a phone number written neatly underneath. The call I made later that afternoon was one of my most serendipitous graduate school moments, leading me to a brilliant scholar of Hindi who would later become my mentor and dear friend. I didn’t know about Ved Vatuk’s university-directed activism when I first met him in 1994. But I felt the effects of it in everyday discussions with fellow graduate students at UC Berkeley, who increasingly voiced concerns about the department’s lack of tenured women and scholars of South Asian descent. When I saw how warmly Dr. Vatuk was greeted by all ages and levels of faculty and students on that busy end-of-the-semester spring day, I couldn’t help but think that Vatuk’s early activism was in many ways a success, leading to the development of more inclusive systems of governance and participation.

(Above):Â Ved Prakash Vatuk speaking at an event in his honor at the Center for South Asia Studies, UC Berkeley.

If there is one idea that could be said to underlie all of Vatuk’s writings, whether poetic or academic, it is skepticism regarding the potential of established political structures to improve the state of humanity. In keeping with his early passion for the field of folklore, Vatuk’s work reflects upon the potential of the “folkâ€â€”or in his own words, “the thousands of little Nehrus and Gandhis spread all over in the villages and towns of Indiaâ€â€” to contest and challenge the saturation of state power, even if only within the localized warp and weft of everyday life. Vatuk’s early work in folklore and linguistics, for instance, focuses not upon the elites who govern, but on the men and women who lead lives that are extraordinary only in their ordinariness: the tired sugarcane workers of Western Uttar Pradesh who survive twenty-four-hour shifts at the presses by singing a special type of work song; the highly skilled yet overlooked performers of local folk operas in eastern Meerut; the poor women of a North Indian village who secure their futures by secretly stashing goods with a Brahman neighbor. Vatuk’s mission is in large part to bring the collective voices of these ordinary actors into scholarship: their songs, their dramas, their conversations. His scholarship thus focuses on the disenfranchised who counter injustice with whatever tools they may have for expressing dissent. And what all people have—even the poorest of the poor—is a voice.

A bottom-up understanding of power is not limited to Vatuk’s academic inquiry; it also serves as the inspiration for much of his poetry. His 2002 epic Bahubali is a case in point, which earned him the Hindi Sansthan’s prestigious Jaishankar Prasad Award for best epic of the year. In this “story-in-verse,†Vatuk portrays the strength of ordinary resistance in his rewriting of a Jain scriptural narrative that tells the story of two feuding brothers. When the elder brother Bharat undertakes to conquer the entire world in the name of peace, his younger brother Bahubali threatens to sacrifice the lives of his subjects in order to protect his kingdom from his elder brother’s aggression. As Vatuk explains when reflecting upon his writing of the epic, the battle between these two feuding brothers “could have been as horrific as the war in Mahabharat, had not the blameless subjects and its leaders stood up to protest the imminent bloodshed of the innocent in the impending dharmyuddh (righteous war).†It is thus the everyday folk, not the kings, who have the experiential wisdom to see through the pointlessness of war and propose a nonviolent alternative.

(Above):Â Sociology Prof. Raka Ray, chair of the Center for South Asia Studies at the University of California at Berkeley, listens as emeritus Prof. Padmanabh Jaini speaks at an event in honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk.

Vatuk’s passion for the revolutionary potential of ordinary citizenship originated in a childhood infused with anticolonialist energy and unrest. The youngest of thirteen children, Vatuk was born on the thirteenth of April, 1932, fifteen years before India won its independence. His concern with social inequality was evident as early as the fifth grade, when he renounced his caste surname and took on his penname “Vatuk.†Inspired by the political poetry of the performing bhajnopdeshaks who came to his village during the annual Arya Samaj conventions, Vatuk began writing folk lyrics on freedom and revolution at only ten years of age. Although his home village was far removed from the bustle of its closest neighboring city Meerut, the struggle for independence informed the lives of even the most isolated, fostering the development of diverse grassroot sentiments that permeated everyday life. Vatuk’s father Krishna Lal, the only Sanskritist Arya Samaji priest in the village, had long engaged in freedom fighting at the local level, particularly with respect to caste discrimination. Foremost to this effort was his founding of the first Arya Samaj temple in the area, established in opposition to the local Shiva temple’s refusal to allow low-caste dalits to worship alongside other villagers. So even though Vatuk celebrates the voices of the progressive folk in his writings, he also recognizes the small-minded potential of popular religious institutions to incite the worst instincts of humanity through religious, ethnic, and gendered fundamentalism and conservatism.

The book launch celebration, organized by Puneeta Kala and Sudev Sheth, began with an introduction by Professor Raka Ray, the current chair of UC Berkeley’s Center for South Asia Studies and also one of the volume’s contributors. Reminding the audience of Gerald Berreman’s characterization of Vatuk as a “truly multicultural renaissance man,†Ray outlined Vatuk’s achievements as the product of “a courageous political and social activist who has tirelessly worked for peace, justice, and equality.â€

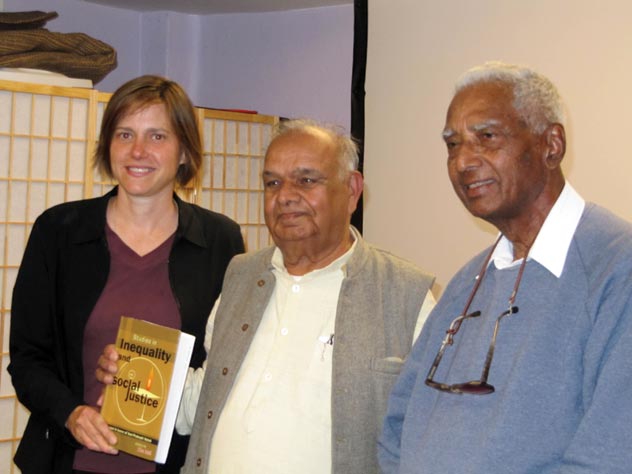

(Above): At the launch of “Studies in Inequality and Social Justice: Essays in Honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk,†at the Center for South Asia Studies, University of California at Berkeley (l-r): Kira Hall, Ved Prakash Vatuk and Padmanabh Jaini.

Professor Padmanabh Jaini then approached the podium to release the book, contextualizing Vatuk’s accomplishments by referencing their friendship at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies back in the late 1950s. Thanking Vatuk for his cooking expertise (Vatuk had apparently provided his friend with many delicious dinners during their time together in London), Jaini offered memorable descriptions of Vatuk’s early political leanings, among them his unceasing concern for the welfare of India’s dalit community. Both of these commentaries set the stage for my own discussion of Vatuk’s life and work, excerpted from the volume’s introduction and repeated in part here. Independent scholar and festschrift contributor Sharat Lin concluded the introductory remarks by expressing appreciation to Vatuk for working with him over the years on issues such as war and racism. Lin said that the most valuable gift he had ever received from Vatuk was a poem that Vatuk had written for his son’s birthday, a gift that remains when more material offerings are gone or broken. Lin’s remarks provided a fitting transition to the poetry reading that was to follow, an event captured in four parts by videographer Jamie Jobb and available for viewing on YouTube.

Vatuk’s reading and discussion centered on the events that have provided the impetus for much of his poetry, among them the Indian freedom movement, the Indian emergency in the mid-1970s, and the early 20th century North American-based Gadar Movement . His disillusionment with India’s political system was evident most overtly in his reading of two poems that he had composed in the mid-1970s for his older brother Sunder Lal, one of the 376 activists who were imprisoned on the first day of erstwhile Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s emergency. Vatuk sent scores of poems to his brother while he was imprisoned for eighteen months, providing him comfort as he sat in solitary confinement in a Varanasi cell. He wrote literally thousands of poems during the Emergency; indeed, during one three-day period alone in the summer of 1975, he reportedly composed over 150 short and long poems. The poems he wrote during this time were later published in three volumes Kaidi Bhai, Bandi Desh (Jailed Brother, Imprisoned Nation), Apat Satak, (One hundred poems of the Emergency, 1977), and the English publication Between Exile and Jail (1978), though many of them circulated underground in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada long before publication.

The seeds of extreme disillusionment that these books of poetry express with respect to the political process had emerged in Vatuk’s political essays decades earlier. His first major essay, written when he was only nineteen years old, was published in 1951 as a lead article in the Sunday magazine section of the widely circulated Navabharat Times. Delivering a scathing critique of the unethical and corrupt practices used by India’s national leaders to win elections, the essay launched Vatuk’s career as a political soothsayer. His adult experiences in Britain and the United States subsequently contributed to the evolution of his political mind. After earning an advanced degree in Hindi literature from Punjab University in 1953 and an M.A. in Sanskrit from Agra University in 1954, Vatuk boarded a ship to London and began work on his Ph.D. dissertation at London University. The realities of British daily life compelled Vatuk to rethink his previous imaginings of both home and abroad, launching his interest in a broader interrogation of structural inequality that considers systems of race as well as those of caste and class.

Vatuk’s move to the United States in 1959 marks the onset of one of his most productive decades with respect to the writing of academic essays. It was during graduate school at Harvard University and his subsequent years at the University of California at Berkeley that Vatuk became increasingly attracted to folklore, a field that shared his discomfort with many of the elitist assumptions that guide academic scholarship. Indeed, the field of folklore had emerged in large part through the rejection of academia’s preoccupation with so-called “high†forms of literature and poetry, a perspective that informs Vatuk’s investigations of both non-standard Hindi dialects and localized performance genres. A tumultuous 1960s American climate also fueled Vatuk’s rebellious artistry as a popular essayist. During this period, Vatuk wrote over 500 essays for Indian publications, addressing such subjects as the civil rights movement, the free speech movement, the anti-Vietnam war movement, and finally, the agricultural labor movement led by Cesar Chavez. He worked in an activist capacity within all of these movements, marching to protest the Vietnam war and participating in political teach-ins. But after his mother Kripa Devi died in 1971, Vatuk ceased writing political essays for the most part, turning his attention back to his first passion, poetry. Indeed, since the death of his mother, Vatuk has written at least one poem a day, without fail. Vatuk remembered his mother fondly during his presentation at the center, noting how she, like so many illiterate persons, exhibited profound bravery during India’s freedom movement.

(Above):Â Sharat Lin, a South Asian community activist, speaking at an event in honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk.

Poetry is usually not the first medium that comes to mind when one thinks of the articulation of a sustained critique against war, but for Vatuk, nothing is more suited to a portrayal of war’s atrocities than a poem. His first book of poetry in English, Silence is Not Golden (1969c), both promoted civil rights and condemned the Vietnam War, reflecting inspiration from a variety of American protest movements. But his most powerful statements against war-inflicted violence are undoubtedly located in his recently published trilogy of epics: Bahubali, Uttar Ram Katha (The Later Life or Ram) and Abhishapta Dwapar (The Cursed Age of Dwapar). In his critical examination of central scriptural narratives, Vatuk illustrates how these texts, far from promoting freedom, instead advocate the enslavement of humanity in the name of dharma. What good is dharma, he asks, if it buries Sita and cannot save Draupadi from torment? What war is not fought in the name of dharma and truth, and what war is there where dharma and truth are not sacrificed? Even though Vatuk’s epics are based on Indian myths, the interpretation that he offers to his readers regarding the unjustifiable relationship between religion and war is both global and timeless.

Vatuk’s skill at uniting aesthetics and social critique is nowhere more evident than in the poem that carries the refrain main nahin manta (I Do Not Accept) , a seven-stanza piece that he read at the conclusion of his UC Berkeley presentation. Originally published in 2000 in the collection Itihas Ki Cheekh (The Cry of History) and reprinted in multiple domains in both India and the United States, this oft-cited seven-stanza poem decries the social institutions that lead to imperialism, injustice, violence, and the exploitation of women and dalits.

Jo dhahata hai nit pyar ka har qila,

Jisse aapas mein koi nahin hai mila,

Woh Kurukshetra ho ya ki ho Karbala,

Bhai bhai ka katega jisse gala,

Aise har dharm ko,

Pap dushkarm ko,

Main nahin manta, main nahin manta.

That which demolishes the castle of love,

That which never lets people unite,

Whether it happens in Kurukshetra or Karbala,

When a brother cuts another’s throat,

All such dharma,

All such heinous action,

I do not accept, I do not accept.

Many members of the audience were highly familiar with this piece and joined Vatuk in reciting the refrain. The May afternoon event thus provided a rare opportunity for colleagues, friends, and admirers to hear Vatuk contextualize the writing of his poetry as a response to varied forms of social inequality. Indeed, it is the rebellious aesthetics that undergird poems like this one that inspired twenty-one scholars to produce a collection of essays in Vatuk’s honor. As the editor of the collection, I hope that its readers will be involved in their own revolutionary activities across the world, both quiet and loud, and I am grateful to UC Berkeley’s Center of South Asia Studies for enabling us to celebrate the life and work of this exceptional man.

Book Information:

Hall, Kira, ed. (2009). Studies in Inequality and Social Justice: Essays in Honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk. Archana Publications, Meerut. 449 pages. The book can be obtained in the USA from the Folklore Institute, P.O. Box 1142, Berkeley, CA 94701-1142.

Links:

The full text of Professor Hall’s introduction to Vatuk’s festschrift is available for download at www.colorado.edu/linguistics/faculty/kira_hall/articles/HALL2009b.pdf.

Jamie Jobb’s four-part video of the South Asia Studies celebration is available for viewing on YouTube at www.youtube.com/watch?v=yesrJ8Hm1TU.

|

Kira Hall, associate professor of linguistics and anthropology at the University of Colorado at Boulder, is editor of “Studies in Inequality and Social Justice: Essays in Honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk.†Kira Hall, associate professor of linguistics and anthropology at the University of Colorado at Boulder, is editor of “Studies in Inequality and Social Justice: Essays in Honor of Ved Prakash Vatuk.†|

|

|

|

|

|