COVER STORY

Jyoti Basu and the Indian Left: Mixed Past, Grim Future

It is a sad commentary that the doctrinaire Indian left failed to learn from the pragmatism and humility of recently deceased communist titan Jyoti Basu, and the arrogance and ineptitude of the post-Basu Left Front leadership in West Bengal portends a grim political future for both the left and the state, writes Partha Banerjee.

(Above): Jyoti Basu in retirement.

(Below): The death of Jyoti Basu, who was chief minister of West Bengal for 23 years, an unmatched record in India, leaves a big vacuum in left politics in India as its previous electoral success, particularly in West Bengal, unravels due to the arrogance and insularity of its more recent leadership.

The Legacy The Legacy

Jyoti Basu, an icon of Indian socialism, died in Kolkata. He was 95. With him, an important era of South Asian politics passed, too.

Even though Basu belonged to the Communist Party of India that called itself Marxist-Stalinist, observers always thought he was more of a social democrat, a practitioner of realpolitik. His lifelong activities and particularly his later years demonstrated a rather moderate, inclusive philosophy that made him well-accepted and respected not just to the hard left in India, but to its splintered progressives, and even to some moderate conservatives. He’s also been a believer of electoral democracy, much to the chagrin of the election-boycotting far left (this is not to say that electoral democracy worked wonderfully in India; in fact, the powerless majority might say it’s been window dressing and validation of the status quo — just like the U.S.). Add to that his personal acumen: vast knowledge and experience about India and world politics, personal integrity, and ability to create and sustain broad coalitions.

These were exceptional attributes for a professional politician, especially in today’s India, that made him the longest-serving chief minister of the state of West Bengal – a once-prosperous state that got the brunt of a British partition and the Bangladesh liberation war with massive bloodshed, a huge influx of refugees and economic crises. In 2000, after twenty-three years as the chief minister of the state, he voluntarily stepped down and handed over the mantle to one of his fellow torchbearers.

Meanwhile, in 1996, when a nationally elected moderate, left-of-center alliance asked him to be India’s next prime minister — the most powerful position in the subcontinent — he sacrificed it because his own Communist Party’s politburo decided not to assume the position on ideological reasons some might call anachronistic. Later, Basu himself called the decision a “historic blunder.” To millions of Indians (including many who do not believe in electoral democracy), he would have undoubtedly been a much more qualified head of the country than most others that came before or after.

As a card-carrying member of India’s Communist Party who got his training both in left politics and law in 1930s London, where he was involved with the anti-imperialist freedom struggle, he practiced and followed leftist rules and dictates ardently. History, however, tells us that even within his own party, he often sided with the moderates, and challenged hardcore policies he found non-pragmatic and out of touch. Other than the 1996 decision not to make Basu the Indian prime minister – one that dashed hopes of left-liberals, students, youth and labor unions, and eventually disempowered Indian progressives and anti-war forces – on significant national and international issues Basu challenged the communist orthodoxy and diehard left. In many instances, he did not succeed: Indian communist parties have had an unfortunate dogmatic penchant of putting international politics before national interest, alienating the middle mass. Example: in the 1960s, just before a devastating Chinese military aggression on Indian borders that killed many soldiers and civilians and humiliated the nation, Basu’s party in its national convention drew up a resolution expressing faith in Chinese communists and their peaceful solidarity with Indian comrades. Basu and his ally E.M.S. Namboodiripad dissented on the party’s position that created major anti-left sentiments in India; right-wing and centrist-capitalist groups exploited it to their advantage. In 1967, a right-center conservative coalition won important state elections for the first time in post-partition India.

(Above): Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh paying homage to the deceased former West Bengal Chief Minister Jyoti Basu in New Delhi Jan. 18. [Press Information Bureau photo]

My own observation is that because Basu and his colleagues’ inclusive realpolitik failed within their own party where doctrine came first and ground reality second, the once-mighty, undivided left in India gradually lost its influence even in stronghold states like West Bengal, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Punjab, broke up in countless factions, became victims of serious, protracted infighting and bloodshed, and in the post-Soviet era, largely became powerless, if not marginalized. Even in states like West Bengal and Kerala where left coalition governments were in power for decades, Jyoti Basu’s departure from active politics created a major leadership vacuum, and a once-unsullied left movement that implemented major land reform empowering landless farmers became synonymous with India’s trademark government inefficiencies, bureaucracies, inertia, hooliganism and corruption. Public sector education, employment and health – three traditional benchmark areas of any supposedly progressive administration – suffered the worst; rampant privatization and an unprecedented socioeconomic divide took place.

Consequently, the next-generation Indian youth that grew up in a make-believe MTV-globalized world with little understanding of working people’s history of struggle, lost respect for any notion of a non-materialist, moderate yet fanaticism-free world, let alone an equity-driven, peaceful society and lifestyle.

Along with it, the vast majority of India’s forever oppressed — rural and urban farm and factory workers, dalits and untouchables, working Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and especially the poorest of the poor women, men and children — lost hope for a dignified life where their children would also share in the advances of the so-called modern, globalized world: where they would also be able to go to the same school as their affluent or upper-caste neighbors, drink water from the same well and go to the same temple, have a dowry-free marriage, or find some basic health care for their ailing, old parents. Where the young women’s rights and respect would not be violated by local musclemen, police, smugglers or mafia.

Today’s “modern and globalized” (call it wealth-crazy) India is sadly an epitome of a class, race, caste, gender, region- and religion-splintered society, where people increasingly believe in violence to combat violence, terror to fight terror. Where harmony is an outdated concept. Unity in Diversity, however rudimentary it was, is a matter of the past. India is now sitting on a live volcano. With the demise of Jyoti Basu and his era of on-the-ground coalition-building politics, chances to put the country back together are now ever so remote.

(Above): A relatively recent photo of former West Bengal Chief Minister Jyoti Basu after he left office. Even in retirement, he was widely respected as an elder statesman.

My Problems with the Indian Left

Let’s take a quick history lesson on Indian politics. Of course, it is only fair to warn the reader that I never belonged to a communist party; I was deeply involved with right-wing politics for over 15 years when Jyoti Basu and the Indian left were at the helm of affairs in my state of West Bengal. Yet, it’s also worth mentioning my total disillusionment and departure from Hindu fundamentalist RSS and BJP that led to my book on the subject. My progressive politics, activism and writing for the past twenty-five years, especially during my living as a graduate student-turned-immigrant in United States is also worth noting.

Although, along with building my own credibility as a grassroots observer both in Indian and American politics, I must confess that I’ve never believed in hardcore left politics, ever more so disbelieved in right-wing politics based on bigotry and hate, and in recent years, I’ve really developed a strong aversion for centrist politics where the elite and privileged run the show keeping the status quo and profit, perpetually disempowering the poor. At the same time, to the disappointment and perhaps some dismay of friends, I’ve been a strong believer of peaceful democratic politics in the U.S., worked hard for a Barack Obama election, and kept faith in his politics of inclusion, in spite of all the problems and missteps his administration has so far caused.

Former Speaker of Indian parliament Somnath Chatterjee, a lifelong Jyoti Basu follower whom the Communist Party of India-Marxist expelled recently on his position on the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal, said after Basu’s death that his party’s decision to pull out of the Congress-led India government was a disastrous one that contributed to the Left Front government’s debacle in West Bengal. He said Jyoti Basu did not support the pull-out.

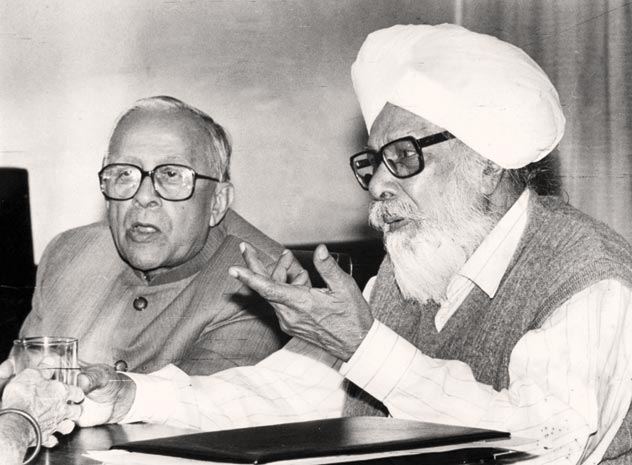

(Above): Jyoti Basu (l) with late CPI-M leader Harkishan Singh Surjeet. Together, the two communist leaders helped an usher in an era of pragmatism and moderation in the CPI-M that got it rich electoral dividends.

I’m not so sure about Chatterjee’s assertion. That’s not the politics of pragmatism I’m talking about. The part of the Indian left that participates in election has stuck with the centrist Congress administration for decades, without ever being an active part of it. Sticking with a centrist, corrupt, pro-rich, inefficient government just to help it be in power has not ever helped the Indian left to increase or assume power of its own. If anything, it has created an illusion that after all, the Congress-led national government is a lesser evil and worth supporting, and pulling out would bring back the right-wing, communal forces leading to more bloodshed.

But that’s only an illusion; the reality is, neither the Congress nor the BJP governments have affected any significant improvements of the lives of India’s 80 percent poor, a large majority of whom have lived in destitution for generations. The Indian left that believes in electoral democracy spearheaded by the two major communist factions CPI and CPI (M) — groups that long separated on pro-Soviet, pro-China lines — once had sharp differences on which national government to support. Pro-Soviet CPI always supported a violently repressive, dictatorial Congress government led by Indira Gandhi, and the once-pro-China CPI (M) and vote-boycotting, more pro-China CPI(Marxist-Leninist) vehemently opposed it. CPI (M) later supported an anti-dictatorship movement led by socialist Jayaprakash Narayan (who also relinquished the position of prime minister) that for the first time helped topple the Congress regime at the national level, to be replaced by a woefully inefficient and ideologically-splintered Janata Party administration, one that Jyoti Basu’s party supported briefly, only to pull out in two years, causing its downfall. Many thought, pulling out of the Manmohan Singh government (one that Chatterjee mentioned) would have the same effect; however, it survived with help from dubious, caste-based politicians – allegedly, with use of massive bribes. CPI(M-L), however, to their credit, always opposed the Congress and Janata Party governments; one might say, their vote-boycotting line would not let them support any elected administration.

In hindsight, my problem with the Indian left has been that I’ve never believed in the politics of disengagement. I see little difference between CPI and CPI(M)’s apparently principled decision not to actively engage in national administrations and that of anti-parliamentary-democracy CPI(M-L) not to support any elected government. On that note, I now strongly support Jyoti Basu’s assessment that not assuming power in 1996 when there was a golden opportunity was indeed a historic blunder. There’s a big difference between that and CPI(M)’s pulling out of the 1977-1980 Janata Party government and 2009 Congress government.

(Above): Archival photo of Jyoti Basu (r), along with other communist leaders, meeting Cuban leader Fidel Castro (2nd from l).

One, Jyoti Basu’s consensus prime ministership would bring together a non-Congress, non-BJP third front, which under his stewardship, would help implement some pro-poor national plans, especially massive land and water reform for the countless landless farmers and enslaved laborers.

Two, even if his government fell under pressure from feudal India, its “modern” capitalists and pressure from West-backed global corporations (the way the Janata Party government fell in 1980), it would be a much more cohesive government implementing policies put together by cohesive, left-of-center forces unlike the left-right tug-of-war Janata Party alliance.

Thirdly, a Jyoti Basu national government would make the abstraction a reality that a moderate left, pro-people, progressive national government is indeed possible in feudal, colonial, caste- and class-ridden India.

By refusing to lead the national government at a critically opportune moment, the CPI(M) leadership failed to take on that challenge and exposed its ultimate weakness; nobody would now believe that this group of people, unlike the right wing BJP and caste-based, corrupt parties, has the courage and strength to live up to expectations. I believe Jyoti Basu’s and CPI(M)’s stock began falling ever since. Basu’s age, failing health and subsequent years of the Left Front administration accelerated the downfall. Many front leaders and workers became synonymous with dysfunction, some otherwise good persons of integrity lost touch with reality on the ground, made serious administrative and policy blunders (culminating in the West Bengal farming-land-giveaway deals with mega-rich corporations, causing a huge uproar and bloodshed among the rural poor), and now in early 2010, it’s almost certain that soon, the three-decade-long Left Front regime is going to be replaced by a centrist Congress government put together by people whose own inefficiencies, lack of administrative and intellectual preparation, massive corruption and politics of muscle power are all too well known. Longtime activists like us shudder at the thought that the dark 1970s days of police repression, anarchy and street violence are inching back to Kolkata and West Bengal.

(Above): JArchival photo of Jyoti Basu in his youth.

Humility and Arrogance

Jyoti Basu donated his body — organs, eyes, everything. It shows his benevolence, care for the needy, and also a scientific, modern, progressive belief — without superstitions or pseudo-religious taboos. It also symbolizes his ultimate sacrifice and dedication of his life for the people he’s left behind.

I never knew Basu well; although as a political worker, first with the right and then with the left, I’ve attended some of his mass meetings when he was still strong just the way the Left Front government was strong. I found his speeches to be confident, simple, clear and easy to understand for the masses. I never heard him using communist jargon and cliches; nor have I heard him using convoluted-confounded reasoning only to prove that he was right. In fact, even when I was a “rising star” in the right-wing student movement, I was deeply impressed with the simple, reassuring style of his speeches. He spoke about peoples’ lives and their problems; he clearly gave directions to resolve the problems with use of his administration and political philosophy.

In fact, I’ve had opportunities to hear Indian leaders from various shades of the spectrum. I’ve closely heard socialist Jayaprakash Narayan, RSS’ Golwalkar and the BJP’s Vajpayee, then-Congress’ “low-caste” mouthpiece Jagjivan Ram (who later quit Congress and joined the anti-Indira Gandhi alliance), and big-ticket Nehru-Gandhi royal family leaders. As a student of public speaking, I always thought both the left and right leaders’ speeches were much closer to the ground than those of the “Gandhi’ite” centrists. Indira Gandhi’s speeches were always full of fluff, rosy promises and little substance. It reminded me of the extremely long, boring speeches of then-Soviet leaders Mikhail Gorbachev or Leonid Brezhnev.

My father’s lifelong involvement with RSS and the BJP (former Jana Sangh) first made me an active worker in right politics. Later, however, when I came out of RSS and its various wings once and for all, I came to know a large number of left leaders and personalities, including my father-in-law and colleagues at a remote, rural Bengal college where I was a biology professor before emigrating to the U.S. At the same time, my maternal uncle Buddhadeb Bhattacharyya — an Indira Congress “rising star” who was later mysteriously shot to death — took me to meet a whole bunch of Congress leaders, and I had a privileged opportunity to see them closely, too. In recent years, I’ve come to know CPI(M)’s stalwart Biman Basu who found time to meet with me on a number of occasions.

I must say, I’ve always found that there are two types of political personalities in India: humble and arrogant. Not that it’s anything extraordinary, considering human nature: personalities come in all shades. But for leaders both in the political arena and family circles, their persona, knowledge, experience, foresight and action plans matter a lot; their ability to build and hold together coalitions of any kind makes or breaks their political mission. It influences not just the contemporary generation, but future generations that watch them. Breaking is easy; building is hard. Role models matter.

In spite of its dedication, tireless grassroots work, promises, action plans and a fertile ground to organize the masses, the Indian left has gradually failed to keep itself together; ideological inflexibility and an unwillingness to compromise has led to disintegration. An extreme arrogance and a refusal to take full responsibility for failures caused its debacle. In late 1960’s, CPI, CPI(M) and CPI(M-L) went their own violent ways; the enormous bloodshed and loss of thousands of young, promising, intelligent lives during the so-called Naxalite era paved the way for massive police repression and eventual destruction of a revolutionary movement. Naxalite leaders’ unrepentant association with the Chinese doctrine, the politics of killing, and an inexplicable opposition to the glorious-yet-bloodstained Bangladesh Liberation struggle made it even more detached from Bengal for generations.

Similarly, after a decade of pro-people, ear-to-the-ground administration led by an energetic Jyoti Basu and his first cabinet members, the Left Front and its countless big and small leaders — urban, semi-urban and rural — slowly started losing touch with reality, and complacency and arrogance reared its ugly head. Our Kolkata metaphor is that after a long, dark Congress era of chaos when there would be blanket power cuts, first there was light (Jyoti means light or radiance), and then again there was no light all over again. I’d like to add one contributing, critical element to that second round of power cuts: the short fuses of left leaders.

The recent forceful land-grabbing for industry-manufacturing that led to massive bloodshed of poor peasants and farm workers (who’ve been the backbone of support for the Left Front for 30 years) is an example of the short fuse. Not only that: unlike a pragmatic, firm yet humble generation of Jyoti Basu that talked less, worked more, found common ground, and would not be embarrassed to admit mistakes, the new-generation personalities — big or small, urban or rural — with their insolence and inability to work together either with the disenchanted masses or overlapping politics, brought both the Indian left movement and administrations they’ve run to the brink of disaster. Worse, the once-impossible-but-now-likely replacement forces in Bengal give good reason to be petrified at the thought of the impending political nightmare.

Add to that the other historic blunder to deprive an entire Bengali generation of English education — a blunder that Jyoti Basu perhaps didn’t ever mention — and we know that the disempowered mass is now even more impoverished, this time intellectually, too. With the onslaught of a pro-West, pro-Wall Street, brainwashing media and an aggressive MTV-generation class that slanders any progressive lifestyle and any concept of equality let alone socialism, the dispossessed, vulnerable class both in West Bengal and elsewhere in India is facing doom. And hunger, despair, suicides, separatist violence and international terror – and more state repression and terror India government-style – are bound to overwhelm South Asia.

Jyoti Basu gave his body and soul to the people. But he is no longer around to stand by their side, to save them from destruction.

|